When I said yes to co-writing a book on surrogacy, I thought it would be just a straightforward application of my general view that moral rights over children, including the right to custody, are grounded in children’s own interests rather than in any interest of the right holder. And in a way it is: in a nutshell, I argue that custody is a prerogative, and hence cannot be sold or gifted. A practice that permits people to transfer it at will is illegitimate. But, along the way, I’m making interesting discoveries; one of them is just how far one may push the analogy between holding slaves and raising children in a world like ours, which has not yet fully outgrown the long tradition of denying rights to children. Many contemporary philosophers of childrearing should find the analogy plausible, even if they don’t share my view about the justification of the right to custody. Let me explain.

You may be familiar with the widespread criticism of surrogacy as a form of child-selling, or child trafficking. This is a very serious charge because, as Bonnie Steinbeck notes, if it’s correct it implies that children of surrogacy are treated like slaves: deemed to be proper object of commercial transactions. One way to resist the charge, particularly popular amongst political philosophers, such as Richard Arneson or Cecile Fabre, is to say that it’s not the child who’s really being bought and sold – or, presumably, gifted in altruistic surrogacy – but merely the right to parent the child, as well as gestational services and, sometimes, gametes. Now, perhaps this defence can be accepted by those who, unlike me, believe that the right to parent partly protects adults’ own interest in being parents. If you have a right to parent – as long as you are competent enough, according to most versions of this view – because the right protects your interest, then maybe you are free to sell, or gift, the right to properly licensed intentional parents. But is this enough to dispel the deeper worry that children’s treatment continues to be, to some extent, on a par to that of slaves? Not really. (“Continues” because our ancestors, the Romans, gave fathers the legal powers to kill, and sell, their children.)

The moral right to custody consists of a bundle of moral rights, some of which are powers over the children. If there is any consensus in the philosophy of childrearing, it is that children may be paternalised, i.e. that some controlling of their lives is not wronging them. The consensus stops here, however, because philosophers disagree about the nature, and therefore the extent, of parents’ moral rights. Again, some believe these rights protect strictly the interests of the child*: others think they also protect some of the parents’ interests – for instance an interest in autonomy. Those who hold the former view also agree that parents’ legal rights far exceed their moral rights. For instance, parents can irreversiblymodify their children’s bodies without medical indication, for religious or aesthetic reasons that children may laterdisown, deny their children medically recommended treatments, enrol them in educational and religious practices independently from how such enrolment serves the child’s interests, paternalise them in excess of what is justifiable given the development of the child’s autonomy, and prevent them from establishing or continuing beneficial relationships. All in all, a lot of morally unjustified controlling!

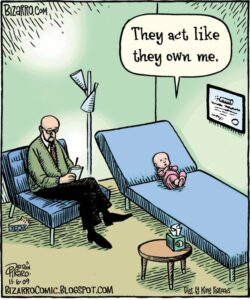

But this is exactly how many of us understand one of the main wrongs of slavery: the holding of unjustified control rights over another person. For neorepublicans, this is the charge against it; and their claim that slaves have a serious grievance even when their masters don’t exercise their rights, drives the intuitive appeal of neorepublicanism. Yet, one need not be a neorepublican to see what’s wrong with some people having unjustified legal rights to control others’ lives.

If so, then in societies where (even licensed) parents hold legal rights in excess of their moral rights, children are, to some extent, morally on a par with slaves. The difference is that the law allows more limited mistreatment of children than it permitted in the case of slaves in slave-owning societies. Moreover, perhaps the arc of children’s history does bend towards justice: the extent of parental legal rights has been shrinking over time. While it’s still bending, those who say that surrogacy is a bit like slave-trafficking have a point. But – and this is not properly appreciated in the literature – their point depends on parenting itself being a bit like slave-holding. A morally very complicated type, moreover: for what is an individual parent to do? Upon reading Pettit, the benevolent slave-owner can free their slaves. But relinquishing custody in favour of the state** would hardly serve the child’s overall interest. Nor can the solution come from universal refraining to have children. The only way, then, is for us to collectively rethink the practices that define childrearing.

* And of third parties, in children who are brought up to be autonomous and properly socialised members of the community.

** Which, in its guardianship capacity, would be bound by the child’s best interest principle.