On the first of January, 2021, the UK’s new “points-based” immigration system came into force. The creation of a “fairer” immigration system, which doesn’t treat EU citizens differently from anyone else, was one of the promises of the current UK government and at least on that count they have delivered: the new rules apply equally to all new would-be migrants (except for those from Ireland, and asylum seekers).

The new rules could, in certain respects, be considered an improvement: there are no longer differential standards for EEA and non-EEA migrants. The general salary threshold is lowered (from £30,000 to £25,600), and the six-year rule which required migrants to either switch into another immigration category (e.g. apply for residency) or leave after six years is removed. These changes are clearly positive from an equalities perspective (even if we can easily imagine an alternative immigration system which would be even better). In this post, I will ask: how fair are the new rules really?

The new points-based system

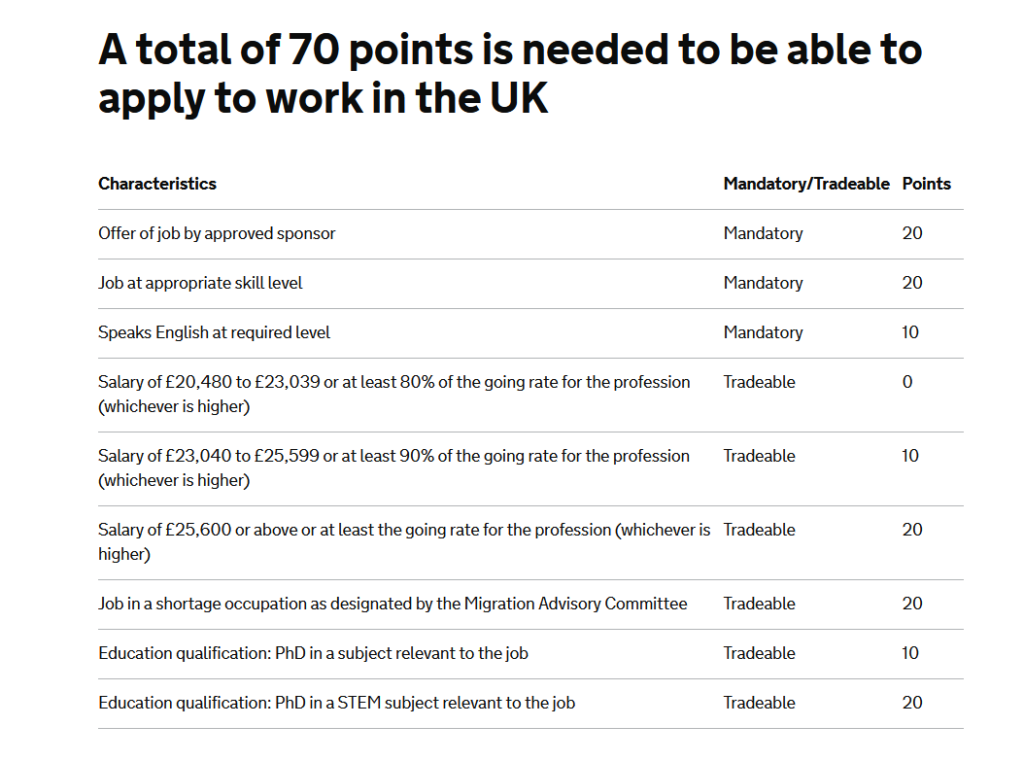

The new system adopted by the UK consists of a number of different routes to entry: the main one, the Skilled Worker route, as well as several other routes for e.g. students, professional sports persons and so on. The Skilled Worker route has three mandatory requirements and a range of additional requirements which are “tradeable”, i.e., failure to meet one can be compensated by meeting another. It’s open only to those who have a job offer from an approved sponsor, and only to those whose job is categorised as sufficiently skilled, which means requiring at least an A-level or equivalent education – care workers, many in the construction industry, many kinds of agricultural workers and many in the hospitality sector are not considered sufficiently skilled and are therefore not eligible for the Skilled Worker visa.

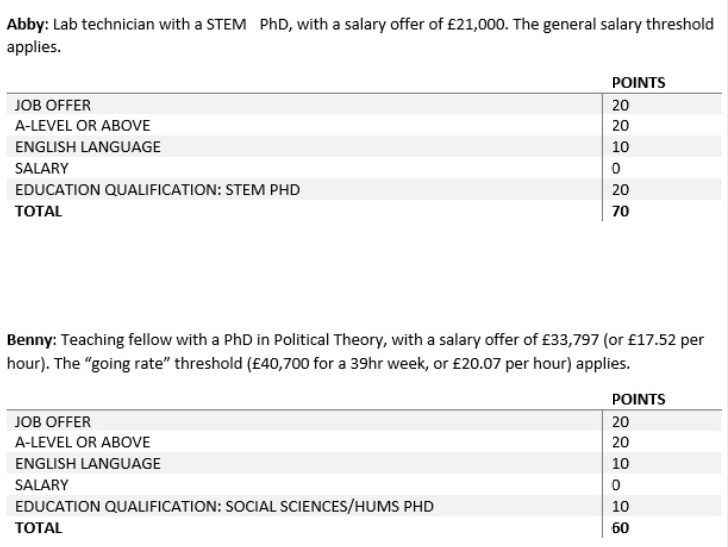

To illustrate, consider the following examples:

- Abby is a lab technician with a PhD. She has a salary offer of £21,000. For lab technicians, the general salary threshold (£25,600) applies. Although her salary offer is less than £23,039 but above the minimum threshold of £20,480.

- Benny has a PhD in Political Theory. He has been offered a post as a teaching fellow, with a salary offer of £33,797 (or £17.52 per hour). For lecturers and teaching fellows in higher education, the “going rate” salary threshold (set at the 25th percentile of the relevant full-time earnings distribution) applies. The going rate for teachers and lecturers in higher education is £40,700 (for a 39hr week) or £20.07 per hour. His salary offer is thus more than the minimum threshold of 80% but less than 90% of the going rate.

How fair is skill-based selection?

In the literature on the justice of immigration restrictions, it’s fairly widely accepted that

- it is (at least sometimes) permissible for states to restrict immigration and

- it is discriminatory and illegitimate for states to restrict immigration on the basis of factors such as race, ethnicity, religion or nationality but

- it is not discriminatory or illegitimate for states to restrict immigration on the basis of skill level or whether a prospective migrant will make a net-positive contribution to the host economy.

To quote David Miller:

The receiving state has certain policy goals – for example, it is aiming for economic growth or to provide its citizens with generous welfare services – and it is entitled to use immigration policy as one of the means to achieve such goals. This explains why selecting immigrants according to particular skills that they can deploy is a justifiable criterion. […] In contrast, selection by race or national background is unjustifiable, since these attributes cannot be linked (except by wholly spurious reasoning) to any goals that a democratic state might legitimately wish to pursue. (David Miller 2016, Strangers in Our Midst: The Political Philosophy of Immigration, pp. 105-06)

However, it’s not entirely clear that skill-based selection is unproblematic.

On the one hand, we may worry that “skill” often functions as a proxy for more problematic bases for selection. In this context, it’s worth noting that the distinction between skilled and unskilled migrants entered into UK immigration law with the introduction of the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act, which distinguished between skilled workers, skilled or unskilled workers with a guaranteed job, and unskilled workers. As David Olusoga shows in his documentary on the Windrush scandal, the distinction between skilled and unskilled workers was explicitly adopted as a proxy for white and non-white workers respectively. In supporting the scheme, Home Secretary Rab Butler stated that

[t]he great merit of this scheme is that it can be presented as making no distinction on grounds of race or colour … although the scheme purports to relate solely to employment and to be non-discriminatory, its aim is primarily social and its restrictive effect is intended to, and would in fact, operate on coloured people almost exclusively. [Emphasis added.]

In a similar vein, education-based discrimination in the Canadian immigration system has been recognised to operate, whether intentionally or not, as a proxy for other forms of discrimination. In the US, it has been observed that the points system “became a veiled way of talking about race”, because of its uneven racial bias against would-be immigrants from the Global South.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that skill-based systems always or even usually are just mere proxies for race-based immigration systems. But, and this leads to my next point, it is important to remember that “skill” isn’t an objective and morally neutral standard. One’s skill level depends on many factors which are not under our control – whether your parents are wealthy or poor, whether you grow up in a good school district or a bad school district, whether high-quality secondary, further and/or higher education is easily accessible or not (and so on) all contribute to how “skilled” we are.

To be more precise, in the case of the UK points-based system, “skill” is essentially a function of two factors: level of education (at least A-level/high-school or equivalent, with additional bonuses for PhDs but only in certain sectors) and salary. Here are some concerns about this approach:

- As the debates surrounding the gender and BAME pay-gap show, salary is a poor proxy for ability. Women and those from most ethnic minorities are, in many sectors, structurally underpaid. Those with physical disabilities too often struggle to command the same salary for the same work as those who are considered able-bodied. By basing the assessment of “skill” at least partially on what amounts to the ability to command a particular salary, this approach risks structurally disadvantaging women, people with disabilities, and BAME individuals.

- The specific system adopted by the UK means that people with disabilities who come to the UK as skilled workers will have no recourse to public funds – i.e., they will not be entitled to the full range of financial support available to resident people with disabilities. This may disadvantage not only those migrants with disabilities who do move to the UK, but may also discourage people with disabilities from pursuing opportunities in the UK which would further their careers.

- The general salary thresholds are not pro-rated. Women and people with disabilities tend to work part-time more often than men. For instance, the Equality Impact Assessment (EIA) of the new rules notes that “13% of men in employment work part-time whilst 41% of women in employment work part-time”, and the general salary threshold may therefore disproportionately affect women and people with disabilities.

- Globally, boys’ and girls’ access to education differs significantly. Requiring at least a high school diploma thus disadvantages women compared to men. More generally, people’s access to education differs significantly across the globe. Skill-based systems may therefore discriminate against those from countries with less-well funded public education systems. Finally, girls are still often discouraged from pursuing careers in STEM. Valuing STEM PhDs over other PhDs thus relatively disadvantages women.

The UK Government explicitly recognises the first three concerns in its EIA (there is no discussion of issues relating to educational requirements). However, it deems the expected differential impacts on women, people with disabilities and BAME individuals as proportionate and necessary.

For instance, it claims that continuing to prevent skilled workers from accessing public funds, despite the potential negative impact on people with disabilities, is justified “due to the necessity of protecting the public finances from migrants travelling to the UK with the purpose of accessing state benefits”. Maintaining the (non-pro-rated) salary thresholds is also deemed necessary: it ensures that, overall, migration has a “net positive fiscal contribution to the economy”. Moreover, it defends the use of going rates and salary thresholds as necessary to prevent exploitation of both domestic and migrant workers. Finally, it claims that the system in general ensures “that migration works in the best interests of the UK resident population”. Any direct or indirect discrimination as a result of these measures is therefore considered justified.

As noted, many distinguish between legitimate immigration restrictions based on skill and illegitimate discrimination based on factors like race. But as we’ve seen, immigration policies intended to stimulate economic growth and to protect access to welfare services for UK residents can discriminate on the basis of gender and physical ability as well as ethnicity and nationality. This is the case even when the use of the skilled/unskilled distinction isn’t intended to discriminate on the basis of such protected characteristics. Rather, it’s the result of how “skill” is measured given that “skill” doesn’t exist in a vacuum. And in the UK case, such discrimination is explicitly accepted as justified with reference to the “best interests of the UK resident population”.

As it turns out, it is not easy to draw a neat line between “fair” selection based on skill and unfair selection based on ethnicity, gender, and so on. This gives rise to a dilemma: either we accept that an immigration system which discriminates against these protected characteristics is permissible as a tool for achieving domestic policy goals such as economic growth, or we maintain that such discrimination is not permissible but at the cost of rejecting skills-based immigration systems – at least those which consider skill in terms of salary and education – as unfair.